Last week, the Federal Aviation Administration intentionally broke part of the 737 Max’s flight control computer. Inside Boeing’s engineering flight simulator in Renton, Wash, test pilots flew a scenario causing a fault in a microprocessor that lives in a box underneath the floor in an electronics equipment bay of the single-aisle jet, according to two people familiar with the situation.

The FAA and Boeing have been putting the Max’s revised Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System software through its paces as part of its on-going struggle to return the jet to service following the crashes of Lion Air 610 in October and Ethiopian Airlines 302 in March that killed a total of 346 people.

“When fixing an aircraft you don’t want to design in the next crash,” said one of the people.

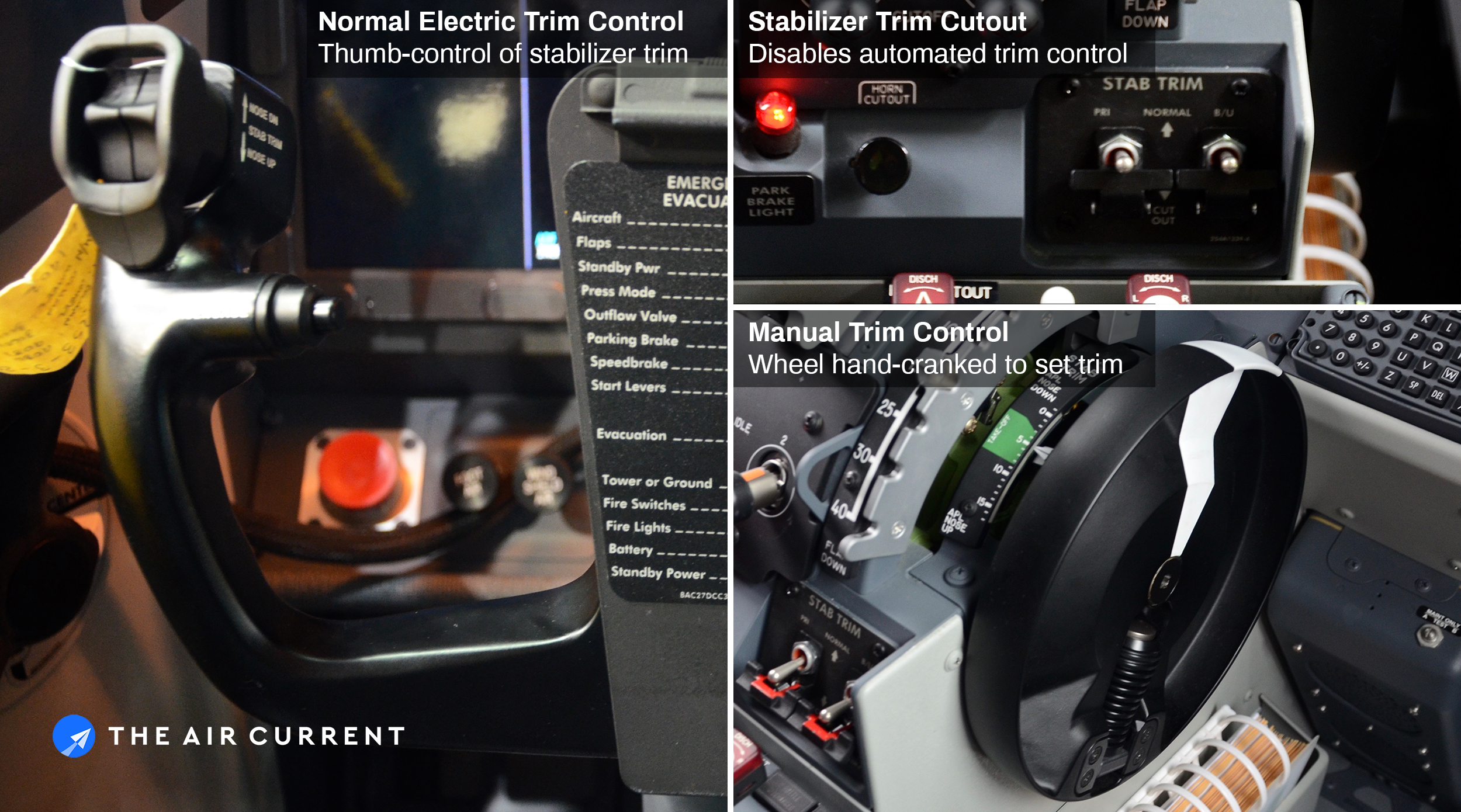

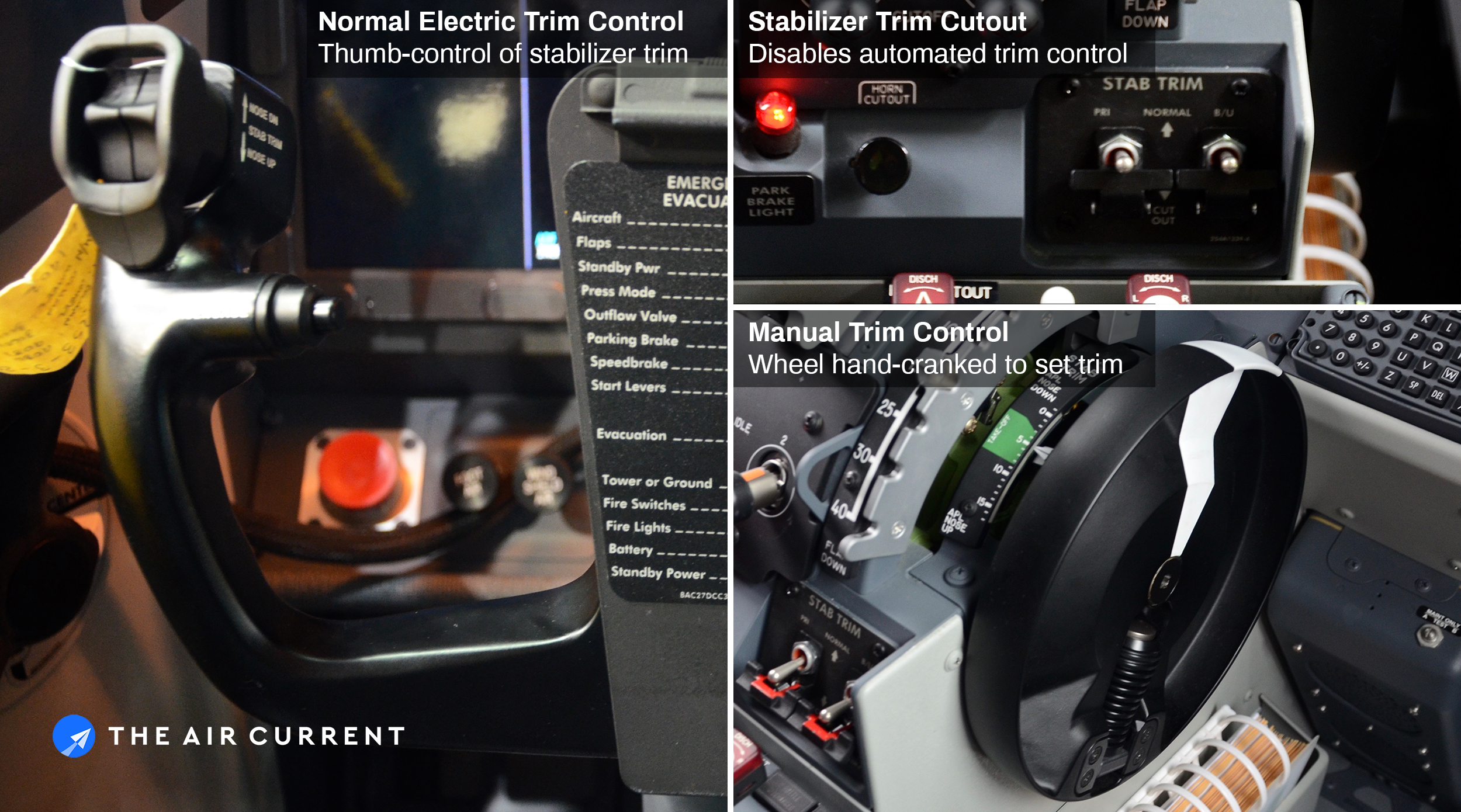

The result, which both people say was expected as part of the scenario, caused the jet’s simulated horizontal stabilizer to move on its own, swiveling the jet’s nose downward as it began to lose altitude in the simulator. The test pilot initiated the runaway stabilizer trim checklist, according to the people, but found the electric trim switches on the pilot’s yoke unresponsive as the stabilizer continued to force the jet’s nose down even further.

Related: What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System?

The deliberately broken microprocessor had become overwhelmed with data from the flight control system, significantly slowing the test pilot’s response to the virtual plunge in altitude. The test pilot ultimately was able to recover control of the aircraft in the scenario, one of the people said, but the system’s unexpected slow response to the proper checklist steps ultimately produced what the FAA has deemed a “catastrophic” situation for the passenger airliner.

Boeing initially had characterized the situation with a “major” rating, one rung below the FAA’s own “catastrophic” assessment, the most serious. Ultimately, the FAA determined the scenario — which itself was unrelated to the activation of MCAS — needed to be fixed before the aircraft could be fully assessed for its return to service. The FAA in a statement said the U.S. aviation regulator ”recently found a potential risk that Boeing must mitigate.”

Related: The world pulls the Andon Cord on the 737 Max

“An average line pilot wouldn’t know what the hell they’re doing,” said one of the people, who said the uncommanded movement was not an erroneous activation of the MCAS function, which has been at the center of the twin crash investigations. The FAA’s view ultimately won the day. Boeing in a statement said it “agrees with the FAA’s decision and request, and is working on the required software.”

But the fix is expected to add months to the jet’s return to service, clouding an already complicated outlook for the 737 Max. Operators of the 737 Max were caught off guard Thursday by the fresh news of the software glitch, according to one large customer, setting back not only the jet’s return to service, but the long road ahead for repairing Boeing’s reputation with both customers and the public. Dennis Muilenburg, Boeing’s Chief Executive, on Wednesday told the Aspen Ideas Conference that felt the aircraft could be back in service by late summer, but that expectation now looks impossible.

Boeing believes the fix can be accomplished with another software modification to re-route data across multiple microprocessor chips in the flight control computer, the people said. However, the complete software package won’t be fixed and ready for final evaluation by the U.S. regulator until at least the “September timeframe,” the person added.

Related: Boeing details changes to MCAS and training for 737 Max

“The FAA is following a thorough process, not a prescribed timeline, for returning the Boeing 737 Max to passenger service,” the regulator added in its statement.

The issue is seen to be unrelated to the existing fleet of Next Generation 737 aircraft, the people noted.

Boeing on Wednesday put out an 8K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, indicating a significant material event fo the aerospace giant.

The FAA “identified an additional requirement that it has asked the company to address through the software changes that the company has been developing for the past eight months,” the company said in a statement, mirrored in the 8k filing. “Boeing will not offer the 737 MAX for certification by the FAA until we have satisfied all requirements for certification of the MAX and its safe return to service.”

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com